A YouTube hot take lately has been shouting that Silent Hill f is some kind of “feminist propaganda” shoehorned into the series. That’s a lazy read, and it falls apart the moment you actually look at the game on its own terms. Silent Hill f sets its scene deliberately: 1960s Japan. The game carries a clear content warning and a developer note saying those depictions reflect the period, and do not represent the team’s own values. That matters, because the setting isn’t some arbitrary backdrop used to push an agenda. It’s the canvas the story needs to exist.

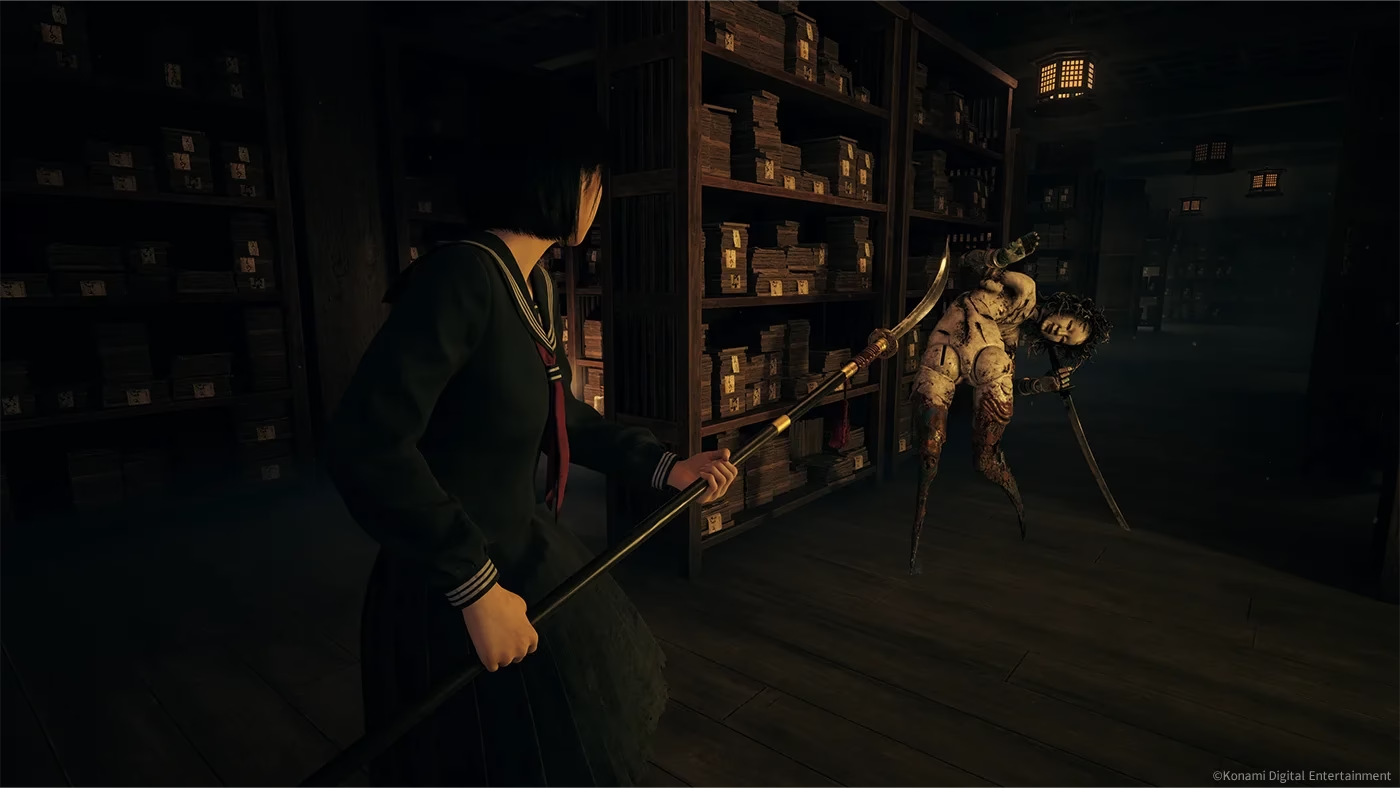

If you know Silent Hill at all, you know the franchise doesn’t trade in modern political manifestos. It trades in personal and cultural trauma. From day one the series has used monsters as mirrors—externalized forms of guilt, fear, repression, and social rot. The creatures are rarely random shocks. They are narrative shorthand for what the protagonists are living through inside themselves and inside their worlds. That’s the franchise DNA. Call it symbolism, call it psychological horror, call it narrative alchemy—whatever you pick, it’s not the same thing as ideological messaging aimed at converting players.

Look at Silent Hill 2. James Sunderland comes to Silent Hill consumed by grief and guilt. The town answers with imagery and foes that reflect his inner state. Pyramid Head is not a political poster. He’s an indictment of James’ repression and self-punishment. That personalized horror is the franchise’s template for how story and symbolism work together. Reduce that to “propaganda” and you’ve ignored the entire point.

Silent Hill 3 is another useful touchstone. Its whole arc is threaded through womanhood, forced roles, bodily horror, and the grotesque politics of reproduction and cultic expectation. Heather’s journey is intimately bound to how gendered fear and exploitation shape her world. The game doesn’t lecture you, it stages the horror and lets you feel it. If Silent Hill has ever examined social injury, it’s done that by making it visceral and personal, not by writing an op-ed and calling it a monster.

Now apply that lens to Silent Hill f. The developers deliberately placed the story in 1960s Japan because that era carries very particular structures of gender, power, and social expectation. When a game dramatizes how women of that era might be boxed into certain roles, or how a teenager could internalize shame and anger, it isn’t “pushing” modern ideology. It’s reconstructing a specific historical psychosocial reality and translating that into horror. That translation is the whole point. Developer interviews and previews make clear the team wanted to explore this new cultural angle rather than shoehorn contemporary talking points into the franchise.

Calling that approach “woke” or “propaganda” misunderstands two things at once. First, it mistakes depiction for endorsement. A story can show ugly beliefs without supporting them. Second, it misunderstands horror as a genre. The best horror doesn’t tell you what to think. It forces you to feel the consequences of actions and systems, then asks what that feeling means. Silent Hill f is following a decades-long lineage in the series that uses setting, symbolism, and psychological dread to do exactly that.

If the critique is stylistic—if someone objects to the game’s pacing, combat, or tone—that’s fair game. Critique gameplay, critique technical performance, critique whether this Silent Hill hits the same existential notes as past entries. But a quick scroll to “woke propaganda” as a verdict is a rhetorical shortcut that skips analysis and goes straight for outrage. It’s easier to scream than to read. Silent Hill’s monsters are never about slogans. They’re about consequences.

That’s the thing I respect about Silent Hill f. It isn’t a lecture. It’s an excavation. The era and its social pathologies are the fossils the game digs up and showcases. The narrative asks us to look, to feel, and to reckon. If the series has taught us anything, it’s that horror can be the clearest mirror for the uglier parts of human life. Labeling that mirror “propaganda” says less about the game and more about the viewer’s impatience with nuance.

Silent Hill f may split fans on tone or mechanics. It may provoke hot takes. That’s fine. But if you want to argue it’s an ideological attack rather than a piece of historical, psychological horror, you’ll need to explain how depiction became conversion. Otherwise you’re just projecting. The game already did the work: it set its time and place, it issued its content warning, and it framed its story as a cultural horror rooted in genuine social dynamics. That’s storytelling, not a manifesto.